Table of Contents

- Introduction to First-Order Circuits

- Components of First-Order Circuits

- Resistors

- Capacitors

- Inductors

- Time Constants and Response Characteristics

- RC Time Constant

- RL Time Constant

- Step Response

- Natural Response

- Analysis Techniques for First-Order Circuits

- Kirchhoff’s Laws

- Nodal Analysis

- Mesh Analysis

- Laplace Transform

- Applications of First-Order Circuits

- Passive Filters

- Power Supplies

- Control Systems

- Simulation and Experimental Verification

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Conclusion

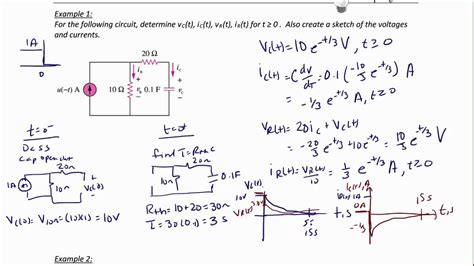

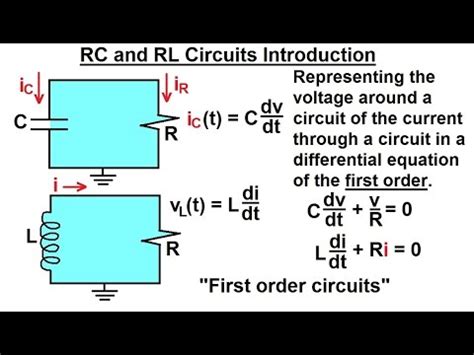

Introduction to First-Order Circuits

First-order circuits are electrical networks that contain only one energy storage element, either a capacitor or an inductor. These circuits exhibit unique behavior in response to input signals, characterized by exponential growth or decay. The presence of a single energy storage element results in a first-order differential equation describing the circuit’s behavior.

The study of first-order circuits is essential for several reasons:

-

Fundamental building blocks: First-order circuits are the foundation for more complex electrical and electronic systems. Understanding their behavior is crucial for designing and analyzing higher-order circuits.

-

Filtering and signal conditioning: First-order circuits are commonly used as filters to remove unwanted frequency components or to condition signals in various applications, such as audio processing, telecommunications, and power electronics.

-

Transient analysis: First-order circuits play a significant role in analyzing the transient response of systems, which is critical in designing control systems, power supplies, and protection circuits.

-

Energy storage and transfer: Capacitors and inductors in first-order circuits store and release energy, enabling various applications such as smoothing power supply ripples, energy harvesting, and resonant circuits.

Components of First-Order Circuits

First-order circuits consist of three main components: resistors, capacitors, and inductors. Each component plays a specific role in the circuit’s behavior and contributes to its overall response.

Resistors

Resistors are passive components that oppose the flow of electric current in a circuit. They are characterized by their resistance, measured in ohms (Ω). In first-order circuits, resistors are used to limit current, control voltage drops, and provide damping. The voltage-current relationship in a resistor is described by Ohm’s law:

V = I × R

where V is the voltage across the resistor, I is the current flowing through the resistor, and R is the resistance.

Resistors can be connected in series or parallel to achieve desired resistance values or to distribute voltage and current in a circuit. The equivalent resistance of resistors in series is the sum of individual resistances, while the equivalent resistance of resistors in parallel is the reciprocal of the sum of reciprocals of individual resistances.

Capacitors

Capacitors are passive components that store energy in an electric field. They consist of two conductive plates separated by an insulating material called a dielectric. Capacitors are characterized by their capacitance, measured in farads (F). In first-order circuits, capacitors are used for energy storage, filtering, and timing applications.

The voltage-current relationship in a capacitor is described by the following equation:

I = C × (dV/dt)

where I is the current flowing through the capacitor, C is the capacitance, and dV/dt is the rate of change of voltage across the capacitor.

Capacitors oppose changes in voltage by allowing current to flow when the voltage across them changes. In a DC circuit, a capacitor acts as an open circuit once it is fully charged. In an AC circuit, capacitors exhibit a frequency-dependent impedance, making them useful for filtering and signal conditioning applications.

Inductors

Inductors are passive components that store energy in a magnetic field. They consist of a coil of wire wound around a core material, which can be air or a magnetic material such as ferrite or iron. Inductors are characterized by their inductance, measured in henries (H). In first-order circuits, inductors are used for energy storage, filtering, and in resonant circuits.

The voltage-current relationship in an inductor is described by the following equation:

V = L × (dI/dt)

where V is the voltage across the inductor, L is the inductance, and dI/dt is the rate of change of current through the inductor.

Inductors oppose changes in current by generating a voltage when the current through them changes. In a DC circuit, an inductor acts as a short circuit once the current reaches a steady state. In an AC circuit, inductors exhibit a frequency-dependent impedance, making them useful for filtering and signal conditioning applications.

Time Constants and Response Characteristics

First-order circuits are characterized by their unique response to input signals, which is determined by the time constants associated with the circuit. The time constant is a measure of how quickly the circuit responds to changes in the input signal.

RC Time Constant

In a first-order RC circuit, the time constant (τ) is the product of the resistance (R) and the capacitance (C):

τ = R × C

The time constant represents the time required for the capacitor to charge or discharge to approximately 63.2% of its final value in response to a step change in the input voltage. After one time constant, the capacitor voltage will have changed by a factor of (1 – e⁻¹), or approximately 63.2%. After five time constants, the capacitor voltage will have changed by a factor of (1 – e⁻⁵), or approximately 99.3%, indicating that the circuit has essentially reached its steady-state value.

RL Time Constant

In a first-order RL circuit, the time constant (τ) is the ratio of the inductance (L) to the resistance (R):

τ = L / R

The time constant represents the time required for the current through the inductor to reach approximately 63.2% of its final value in response to a step change in the input voltage. After one time constant, the inductor current will have changed by a factor of (1 – e⁻¹), or approximately 63.2%. After five time constants, the inductor current will have changed by a factor of (1 – e⁻⁵), or approximately 99.3%, indicating that the circuit has essentially reached its steady-state value.

Step Response

The step response of a first-order circuit refers to the output of the circuit when the input is a step function, which is a signal that changes instantaneously from one level to another. In an RC circuit, the step response of the capacitor voltage is an exponential function that rises or falls towards the final value, depending on whether the step input is a rising or falling edge. The time constant determines the rate at which the exponential function rises or falls.

Similarly, in an RL circuit, the step response of the inductor current is an exponential function that rises or falls towards the final value, depending on the polarity of the step input. The time constant determines the rate at which the exponential function rises or falls.

Natural Response

The natural response of a first-order circuit refers to the behavior of the circuit when the input is removed, and the circuit is allowed to return to its initial state. In an RC circuit, the natural response of the capacitor voltage is an exponential decay, where the voltage across the capacitor decreases towards zero with a time constant determined by the product of the resistance and the capacitance.

In an RL circuit, the natural response of the inductor current is an exponential decay, where the current through the inductor decreases towards zero with a time constant determined by the ratio of the inductance to the resistance.

Analysis Techniques for First-Order Circuits

Several analysis techniques can be used to study the behavior of first-order circuits and determine the voltages and currents in the circuit. These techniques include Kirchhoff’s laws, nodal analysis, mesh analysis, and the Laplace transform.

Kirchhoff’s Laws

Kirchhoff’s laws are fundamental principles that describe the behavior of voltages and currents in electrical circuits. Kirchhoff’s current law (KCL) states that the sum of currents entering a node is equal to the sum of currents leaving the node. Kirchhoff’s voltage law (KVL) states that the sum of voltages around any closed loop in a circuit is equal to zero.

Using Kirchhoff’s laws, you can set up a system of equations to solve for the unknown voltages and currents in a first-order circuit. This method is particularly useful for simple circuits with a small number of components.

Nodal Analysis

Nodal analysis is a technique used to determine the voltages at each node in a circuit with respect to a reference node, usually ground. This method involves applying Kirchhoff’s current law at each non-reference node and expressing the currents in terms of the node voltages using Ohm’s law and the voltage-current relationships of capacitors and inductors.

The result is a system of linear equations that can be solved to find the node voltages. Once the node voltages are known, the currents through the components can be easily calculated using Ohm’s law and the voltage-current relationships.

Mesh Analysis

Mesh analysis is a technique used to determine the currents flowing through each mesh (loop) in a planar circuit. This method involves applying Kirchhoff’s voltage law around each mesh and expressing the voltages in terms of the mesh currents using Ohm’s law and the voltage-current relationships of capacitors and inductors.

The result is a system of linear equations that can be solved to find the mesh currents. Once the mesh currents are known, the voltages across the components can be easily calculated using Ohm’s law and the voltage-current relationships.

Laplace Transform

The Laplace transform is a powerful tool for analyzing the behavior of first-order circuits in the frequency domain. It converts the time-domain differential equations describing the circuit into algebraic equations in the frequency domain, making the analysis more straightforward.

Using the Laplace transform, you can easily determine the transfer function of the circuit, which relates the output of the circuit to its input in the frequency domain. The transfer function provides valuable insights into the circuit’s frequency response, stability, and transient behavior.

To analyze a first-order circuit using the Laplace transform:

- Convert the circuit’s time-domain differential equations into the frequency domain using the Laplace transform.

- Solve the resulting algebraic equations to find the transfer function of the circuit.

- Analyze the transfer function to determine the circuit’s frequency response, poles, and zeros.

- If needed, use the inverse Laplace transform to convert the results back into the time domain.

Applications of First-Order Circuits

First-order circuits find applications in various domains, including passive filters, power supplies, and control systems.

Passive Filters

Passive filters are circuits that use passive components (resistors, capacitors, and inductors) to attenuate or amplify specific frequency components of a signal. First-order RC and RL circuits are commonly used as low-pass and high-pass filters, respectively.

In an RC low-pass filter, the capacitor acts as a short circuit for high-frequency components, allowing them to be shunted to ground, while the resistor limits the current at low frequencies. The cutoff frequency of the filter is determined by the time constant of the circuit (fc = 1 / (2πRC)).

In an RL high-pass filter, the inductor acts as a short circuit for low-frequency components, allowing them to pass through, while the resistor limits the current at high frequencies. The cutoff frequency of the filter is determined by the time constant of the circuit (fc = R / (2πL)).

Power Supplies

First-order circuits are used in Power supply design for various purposes, such as voltage regulation, ripple filtering, and surge protection. RC and LC circuits are commonly used in Power Supply Filters to reduce the ripple voltage and improve the overall quality of the output voltage.

In a capacitor-input filter, a large capacitor is connected in parallel with the load to smooth the output voltage by storing energy during the peaks of the rectified voltage and releasing it during the valleys. The RC time constant of the filter determines the amount of ripple reduction achieved.

In an LC filter, an inductor is connected in series with the load, and a capacitor is connected in parallel with the load. The inductor acts as a short circuit for DC and low-frequency components, while the capacitor acts as a short circuit for high-frequency components. The LC combination forms a low-pass filter that attenuates the ripple voltage and provides a smoother output voltage.

Control Systems

First-order circuits are used in control systems to model the behavior of various components and systems, such as sensors, actuators, and thermal systems. The first-order differential equations describing these systems can be used to design controllers and analyze the stability and performance of the overall system.

For example, a first-order RC circuit can be used to model the behavior of a temperature sensor, where the resistance represents the thermal resistance, and the capacitance represents the thermal capacitance of the sensor. The time constant of the circuit determines the response time of the sensor, which is crucial in designing temperature control systems.

Similarly, a first-order RL circuit can be used to model the behavior of an electric motor, where the resistance represents the winding resistance, and the inductance represents the winding inductance. The time constant of the circuit determines the response time of the motor, which is important in designing motor control systems.

Simulation and Experimental Verification

To gain a deeper understanding of first-order circuits and verify the results of mathematical analysis, it is essential to perform simulations and experimental measurements.

Circuit simulation software, such as SPICE (Simulation Program with Integrated Circuit Emphasis), allows you to create virtual models of first-order circuits and analyze their behavior under various conditions. By running simulations, you can observe the voltage and current waveforms, measure the time constants, and verify the frequency response of the circuit.

Experimental verification involves building physical prototypes of first-order circuits and measuring their performance using test equipment such as oscilloscopes, function generators, and multimeters. By comparing the measured results with the theoretical predictions, you can validate the accuracy of your analysis and gain practical insights into the behavior of the circuit.

When performing experimental measurements, it is essential to consider the limitations of the test equipment and the potential sources of error, such as component tolerances, noise, and loading effects. Proper calibration and shielding techniques can help minimize these errors and ensure accurate results.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

-

What is the difference between a first-order RC and RL circuit?

A first-order RC circuit consists of a resistor and a capacitor, while a first-order RL circuit consists of a resistor and an inductor. The main difference lies in their response to input signals and their energy storage mechanisms. In an RC circuit, the capacitor stores energy in an electric field, and the time constant is determined by the product of the resistance and the capacitance (τ = RC). In an RL circuit, the inductor stores energy in a magnetic field, and the time constant is determined by the ratio of the inductance to the resistance (τ = L/R). -

How do I determine the time constant of a first-order circuit?

The time constant of a first-order circuit depends on the type of circuit and the values of its components. For an RC circuit, the time constant is calculated as τ = RC, where R is

No responses yet